Fatima's Knight

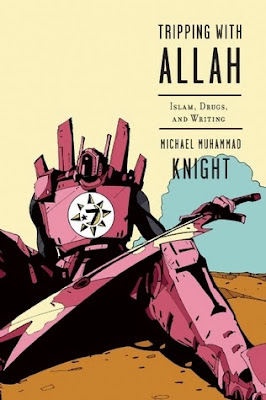

One of the most interesting books about religion that I’ve

read in recent years came from an unexpected angle. Michael Muhammad

Knight’s Tripping with Allah: Islam,

Drugs, and Writings is a brilliantly written and highly intelligent piece

of autobiographical literature, from the pen of an author who combines deep

personal involvement in Islam with an off-the-charts heretical attitude,

profound familiarity with academic research and theory in the study of

religion, and most of all, a truly original, independent, and passionate mind. The troubled son of a white supremacist and paranoid psychotic rapist, Knight was

raised as a Roman Catholic by his mother but converted to Islam at age 16,

after reading the Autobiography of Malcolm X. He went on to study Islam at Faisal Mosque in Islamabad,

Pakistan, and came close to joining the Chechnyan war against Russia. Having

become disenchanted with Islamic orthodoxy, he started experimenting with a

range of alternative Muslim identities, including the Nation of Islam (he is fascinated by its mysterious founder Fard Muhammad) and the Nation of Gods and Earths, also known as the Five

Percenters (who proclaim the divinity of human beings and therefore address

one another, amusingly enough, as “god”). Parallel to this, he also embarked on

a semi-professional wrestling career, subjecting himself to grueling training

routines and diets and finally getting beaten up seriously (fifty stitches!) in

a fight with a notorious wrestler named Abdullah the Butcher.

Tripping with Allah

(an “adventure book for academics to chew on”, p. 30) is the most recent of a

series of nine volumes that document Knight’s continuing search for his

personal, religious, and (not in the last place) masculine identity. Right from the outset, we

encounter him at the intersection of various overlapping cultural contexts and

discourses, including traditional Islam (both Sunni and Shia), the cool hip hop Muslem culture associated with the Five Percenters, Religious Studies as practiced at Harvard

Divinity School, superhero video games and TV comic series such as the 1970s

series Transformers, the parallel

universe of American wrestling and, last but not least, the (neo)shamanic

practice of drinking ayahuasca. Having heard about the spectacular visionary

and healing powers of this famous psychoactive brew from the Amazon forest,

Knight decided to try it – hoping perhaps to see visions of “Muhammad on a flying

jaguar” (p. 4) or perhaps, far more seriously, to find a way of healing his

traumas and find answers in his spiritual quest.

A major theme in Tripping

with Allah is the acute conflict between Knight’s quest for religious

meaning and belonging, and the implications of his academic training in the study of religion.

In the first chapter (“Cybertron Kids”) we find the author and his friend Zoser

watching and “building” (in Knight’s delightful rendering of Five Percenters’

lingo) on an early Transformers

episode called “Dinobot Island”, in which some kind of time warp phenomenon

opens up portals through which life forms from other time periods enter and

start messing with our world. In Knight’s narrative, Dinobot Island becomes a

metaphor for contemporary religion and the pervasive phenomenon of decontextualization

in a globalized media context: for young Muslims like Zoser and himself, and whether they

like it or not, Islam has essentially become a reservoir of traditional materials and

stories to pick and choose from at will, and available for being combined

creatively with anything else that is available, whether it’s hip hop, science

fiction, wrestling, shamanism, or popular comics. In Knight’s words,

“‘Muhammad’ is a superhero template, his sunna

functioning as a How to Be the Perfect Human kit that you’ll never finish:

Muhammad as M.H.M.D., or Masters His Motherfucking Devils.” (p. 9).

And that, of course, is what the book is ultimately all

about. While building up a narrative to prepare the reader for his encounter

with ayahuasca, Knight offers erudite and sometimes brilliant reflections

on a variety of relevant topics, such as the popular depiction of both drugs

and Islam as the demonized “other” of white American identity (“Civilization

Class”), the history of Islamic attitudes towards drugs, including coffee (“Islam and Equality” - “equality”

being a code for hashish - ; “Coffee consciousness”), prophecy

and visionary consciousness according to Avicenna and al-Ghazali (“Avicenna and

the Monolith”), and the intellectual and existential dilemmas of studying

religion academically at Harvard while also practicing it as a Muslim

(“Jehangir Allah”, “Scholars and Martyrs”). Last but not least, there is the conflict

between his emerging identity as a professional scholar of religion and the

primal forces that drive him as a writer. Identifying with one of his heroes, a

brutal wrestler known as “Bruiser Brody”, Knight is worried that the politically correct attitudes and pseudo-intellectual language (for some edifying examples of mindless cultural studies lingo, see pp. 134-135!) that seem

to dominate American academia might finally end up killing his soul:

“Two years have passed at

Harvard, and now I try to picture Bruiser Brody obsessed with explaining

himself, apologizing for himself, justifying his existence through the use of a

larger tradition and perhaps a grounding in theory, trying to find legitimacy

as a public intellectual. I see Bruiser Brody understanding himself through

Roland Barthes, wearing a corduroy blazer and tying back his hair and

insisting, “I’m so much more than just a psychotic chain-swinging freak, if you

read me in my proper context,” dipping out of the personality game while he’s

still ahead and focusing on pure scholarship from this moment on – Bruiser Brody

with his forehead full of scars disappearing into the quiet soft darkness of

those Widener Library stacks and never coming back out” (p. 145-146).

Eventually, Knight has an intake meeting with an American

member of the Brazilian Santo Daime church, which uses ayahuasca as its

sacrament (“Bumblebee”; for the origins of the church, founded by a Brazilian rubber tapper after his visionary encounter with the “Queen of the Forest”, see his informative

chapter “Church Fathers and Mothers”). He finally gets to drink ayahuasca at a

Santo Daime meeting in a private home, but I will not spoil the book for you by

describing how that experience turns out for him. Let me just note that

Knight’s mind and subconscious, filled with Islamic imagery, does not match

very well with the predominantly Christian Catholic setting. It is only at his

third attempt, in a “Western shamanic” setting, that he has a full ayahuasca

experience.

Verbal depictions of entheogenic experience are notoriously

boring, but Knight’s account is an exception to that rule. The 17th

chapter of his book (“Al-Najm”, “the Stars”: see the account of Muhammad’s

ecstatic ascent/descent described in the Quran, Sura 53:1-18) contains a

uniquely precise, impressive, and moving description of visionary therapeutic

healing through ayahuasca – more convincing and instructive than any similar account that I know from the literature. Clearly it is not enough to have a powerful

experience: to bring it across requires a powerful writer as well. Again, therefore, one needs to read this in the original, but given Knight’s biography it will perhaps come as no surprise that this decisive visionary sequence was grounded in Islamic imagery and mythology and went straight for what he needed most: “Out of nowhere, the drug interrupted my book about drugs and spoke instead about broken masculinities” (p. 257). Traumatized through extreme male violence, Knight’s life had been one desperate quest for masculine role models, from the frankly demonic exemplar that had raped him into existence, through the caricatural “He Men” of American wrestling, to the supreme male superheroes of his religious imagination: Muhammad the prophet, Ali the warrior, Husayn the martyr (p. 206). But by the time he drinks ayahuasca, he seems to have reached the end of that road: “It feels like I can’t go anymore; I’m like Macho Man at the end of his run” (p. 186, referring to Randy “Macho Man” Savage, the greatest professional wrestler of the 1980s: see chapter “Macho Madness”). And so it is fitting that the divine saviour/healer and psychopomp (“guide of souls”) who meets him in his vision and shows him the source of true power is not yet another muscle man, but a woman: Fatima, the daughter of the prophet, wife of Ali, and mother of Husayn.

In an interview with Deonna Kelli Sayed, Knight remarks that his Al-Najm chapter is “possibly the most heretical, blasphemous, challenging stuff that I’ve ever written. I don’t spare any of the details”. And that is true: the visionary episodes are sexually explicit, and put an intensely personal spin on traditional Islamic myth and imagery. In other words, the entire healing process would seem to happens on Dinobot Island, through a remarkable collaboration between Santo Daime’s Queen of the Forest and the Islamic Daughter of the Prophet - bien étonnés, no doubt, de se trouver ensemble... And yet, in the same interview, Knight continues by noting that the experience “leads me to this somewhat conservative place, because where I’m at right now, I pretty much just want to read hadith all day”.

Perhaps this will prove to be just a phase in Knight’s continuing story. But then again, he might well be in the process of leaving Dinobot Island, with Fatima’s help: “You can deconstruct Islam, but at some point you have to put it back together. Get your readings grounded in something” (p. 7). In what? The answer seems clear: Knight finds it in an intensely personal experience of divinity, or gnosis, mediated or facilitated by a “tradition”, with all the stories and images that it can provide. He does not find it in the intellectual practice of Quranic exegesis, so attractive and seductive “for the boys” (p. 224, 226, 238), but in a direct encounter with divine Otherness - with a presence, in other words, that is so different from his own identity that it can speak to that identity with unquestionable power and authority. Tripping with Allah may be all about Islam, Drugs, and Writing - but first and foremost, I would suggest, it is a primary source of Islamic mysticism.

In an interview with Deonna Kelli Sayed, Knight remarks that his Al-Najm chapter is “possibly the most heretical, blasphemous, challenging stuff that I’ve ever written. I don’t spare any of the details”. And that is true: the visionary episodes are sexually explicit, and put an intensely personal spin on traditional Islamic myth and imagery. In other words, the entire healing process would seem to happens on Dinobot Island, through a remarkable collaboration between Santo Daime’s Queen of the Forest and the Islamic Daughter of the Prophet - bien étonnés, no doubt, de se trouver ensemble... And yet, in the same interview, Knight continues by noting that the experience “leads me to this somewhat conservative place, because where I’m at right now, I pretty much just want to read hadith all day”.

Perhaps this will prove to be just a phase in Knight’s continuing story. But then again, he might well be in the process of leaving Dinobot Island, with Fatima’s help: “You can deconstruct Islam, but at some point you have to put it back together. Get your readings grounded in something” (p. 7). In what? The answer seems clear: Knight finds it in an intensely personal experience of divinity, or gnosis, mediated or facilitated by a “tradition”, with all the stories and images that it can provide. He does not find it in the intellectual practice of Quranic exegesis, so attractive and seductive “for the boys” (p. 224, 226, 238), but in a direct encounter with divine Otherness - with a presence, in other words, that is so different from his own identity that it can speak to that identity with unquestionable power and authority. Tripping with Allah may be all about Islam, Drugs, and Writing - but first and foremost, I would suggest, it is a primary source of Islamic mysticism.

sounds amazing, especially because it is biographical. A must read, than you professor for the review.

ReplyDeleteFatima's knight? Hardly. More like neoCon extraordinaire Daniel Pipes' golden boy and provocateur per MMK's own admission in William S. Burroughs vs. the Qur'an, 2012, 105-6. Then we have the even more alarming bombshell regarding the political company he keeps and the conferences that invite him to speak as an "expert" in the chapter "Snakes of the Grafted Type" (187-204) in Tripping With Allah itself, which you are reviewing here.

ReplyDeleteSeriously, this gushing, over-enthusiastic endorsement by someone of your Western Ivory Tower reputation and calibre lacks credible objectivity -- makes you look disingenuous in the process -- and is likewise extremely, extremely suspicious, Professor Hanegraaf, not to mention smacking of (if one may say so) of a form of professional grooming and profile building of MMK on your part that may be construed as a blatant form of political cronyism to any objective observer. You say, for example, regarding his credentials, that he displays "...profound familiarity with academic research and theory in the study of religion..." Where exactly, pray tell, is this remotely in evidence within the pages of Tripping With Allah that you are reviewing above or, for that matter, in any of his other writings? Given that MMK does not offer a single citation or footnote for anything he says in almost all of his pop lit (and this is what his corpus of writings really are, and not scholarship), can you kindly cite evidence from his other writings where this may be in evidence? And since there is no evidence for these sorts of credentials you are attributing to MMK in his popular writings, why are you then saying it?

I have known MMK and his work a lot longer than you, Professor Haanegraaf, plus there is a direct connection to the book you are reviewing and myself personally since MMK obliquely and not so obliquely refers to the Fatimiya Sufi Order as well as myself in the pages of Tripping With Allah. This entire project came about as a direct consequence of online interactions between MMK and I (more like one way, where MMK would follow me around assorted online Ayahuasca and entheogenic fora and then later take things I said and make a narrative out of it for his book) as well as interactions with his former friend (and hip-hop artist and DJ), Propaganda Anonymous, who is the real-life Zoser character in Tripping With Allah and who first introduced me to MMK in 2010. Propaganda Anonymous interviewed me for Reality Sandwich in 2010.

Now, a lot of the entheogenic visions and narratives in that book are actually material that MMK lifted wholesale off of the old Ayahuasca forums, many from the old Fatimiya Sufi Order board specifically (defunct as of 2011). So this work is not a work of non-fiction, let alone anthropology or anything else remotely at the level of social science. It is rather a work of pure creative writing (with heavy plagiarism) where MMK has taken bits and pieces from things he has seen and heard online from other people and then crafted it into a work of fiction. He himself really does not assert otherwise either.

However, as I have said to you elsewhere, the only reason it appears that you are enthusiastic about MMK and his work is purely because he is a white American talking about alternative Islamicate discourses and lifeworlds. As if only a white American can elicit credibility about these things in the eyes of his other Anglo-European colleagues. If MMK had been a native (say, from Iran, Pakistan or somewhere else in the Islamic world), you and your other Anglo-European Ivory Tower colleagues would never exhibit even a fraction of the same kind of enthusiasm that you are about this guy. And this is the bottom line, truth of the matter.

[to general readers would may be wondering where this is all coming from: mr Wahid Azal is here continuing a polemic against me that he started on Facebook last week, triggered by the fact that I wrote I was looking forward to MMK's forthcoming book on Magic and Islam] Mr Wahid Azal, let me repeat once more that I'm not your enemy. I'm sorry that you keep writing as though I am, in spite of all my attempts to make peace with you and have a civil conversation in spite of your provocations. I object to the racist assumption, on your part, that the color of my skin or my Dutch/European ethnicity automatically makes me complicit in the Western imperialist project responsible for "spilling oceans of blood and trivializing entire cultures" (your words). You're perfectly correct about those sins of imperialism, but perfectly wrong in assuming that I have even the slightest bit of sympathy for them. Nothing could be further from the truth.

ReplyDeleteProfessor Hanegraaff, you are widely perceived as an ideological and political gatekeeper in the academic study of esotericism in the West. You were once also perceived as a protege of Antoine Faivre before you apparently broke with him. You also nearly derailed the PhD of a friend of mine some years ago to whose dissertation you were an external examiner: an individual parallel universes beyond anything Michael Muhammad Knight is about or knows. Luckily you failed on that score and this person has since gone on to do good things outside of the straight-jacketed and heavily controlled discourse and politicized environment that is the Western Ivory Tower: gatekeeping which regularly stifles certain discourses on ideological grounds and promotes others on the same ideological grounds, which you are doing with MMK. Karen Claire-Voss also gave me the full lowdown on you some years ago; I have also read everything you have published so far; so I know how you roll.

DeleteNow, given that out of hundreds of far more talented contemporary writers and thinkers on alternative Islam and Islamic occultures -- many of whom are natives -- you specifically gush over Michael Muhammad Knight (who is widely, and correctly in my view, is perceived to be a shill), this says one thing only to those of us who understand what the politics revolving around all this is really all about. So, again, I will reiterate (and you are welcome to deny it), had Michael Muhammad Knight been a native -- or, better, if MMK was not the poster boy of certain political agendas and also did not have US east coast publicists and multimillion dollar publishing contracts and agencies at his beckon call -- you would not exhibit the same kind of uncritical enthusiasm for him that you are. It really is that simple and this really is about capitalism in its most banal form. And, yes, your Dutch pedigree together with your gatekeeper capacity in the Western academic knowledge industry -- which as Henry Giroux has proven is an extension of the Western military-industrial-corporate-surveillance complex -- makes you 100% complicit in contemporary imperial Western neo-colonialism, since it is its weltanschauung that you promote and are a professional gatekeeper to in the Western Academy.

Finally, let me underscore another thing: while your credentials in the academic study of Western esotericism and spirituality may be well established, you possess no credentials on the subject whatsoever where Islamicate traditions are concerned. Given this, I am putting you on notice: if this quite unseemly and highly suspicious promotion of MMK by you continues in this vein, you will be contending with me and a host of others who believe as I do in print. Our Tradition is not yours to gatekeep, taxonomize and ultimately trivialize while hiding behind the skirt of Michael Muhammad Knight and for the benefit of Western Anglo-American agendas to further subvert our culture and our collective knowledge.

OK mr Azal, I'm done with your threats and hostitilies. I'll write a few lines in response because this blog is public and general readers will wonder what is going on. You're badly informed if you think I ever broke with Antoine Faivre. I've never been his "protege", but Antoine and I have been close friends and colleagues ever since 1992 and remain so up to the present day. You're obviously welcome to dislike my approaches to scholarship in esotericism, or disagree about MMK or any other topic; but if there's any "ideology" or "gatekeeping" here, those terms clearly apply to your attitude, not mine. Contrary to you, I'm interested in open discussion on a basis of mutual respect. I hardly need you to remind me that I'm obviously not a specialist in Islamicate tradition (but perhaps I'm permitted to have a genuine interest in them, in spite of the colour of my skin or my Dutch ethnicity?) Finally, don't flatter yourself that I might feel intimidated by you threats of public attacks. You're welcome to write whatever you want, and I will surely continue writing whatever I want. Our discussion on this particular blog is hereby over.

ReplyDeleteMike Knight is a plagiarist. This is true regardless of whether he is a "shill" or not. The fact is that he takes ideas from those he latches himself onto and then purports, in print, that these ideas are his. This is what people should really know about this guy. He is a snake.

ReplyDeleteTo be fair, Dr Hanegrraff was a protégé of the respected Dutch scholar Roelef van den Broek, not Antoine Faivre. While Wouter's polemics regarding esotericism are well known, he has never professed to be particularly knowledgeable about Islam and I doubt anyone would regard him as an authority on the religion even in a broad sense of the word. He is far more well-versed in Calvinism.

ReplyDeleteWhat do you mean by my "polemics regarding esotericism"?

DeleteYes, that was "perfectly fair" Titan.

ReplyDeleteWell, the polemics comment was politely explained apparently but it has disappeared. Don't know where this Titan stuff came from. On a different note, a number of Muslims are white [hardly surprising since there are 1.4 billion of them, lol] so why the color of your skin should matter is a bit baffling.

ReplyDeleteBy the way, Professor Azal, that guy whom you mention is not the only one whose work he has tried to derail. Fortunately, in the case of one of my colleagues, Dr Hanegraaff's efforts did not amount to anything. This colleague went on to do some very important work.

ReplyDelete