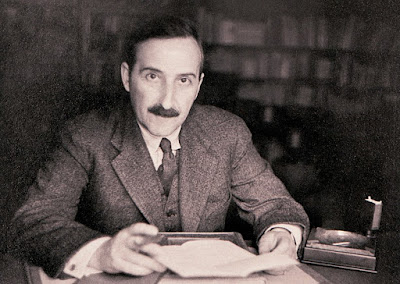

Imaginary Homelands: Stefan Zweig, Gershom Scholem, and George Prochnik

|

| George Prochnik |

Two great Jewish writers and intellectuals of the twentieth

century, Stefan Zweig (1881-1942) and Gershom Scholem (1897-1982): on one side we have the

cosmopolitan advocate of humanistic tolerance, mutual understanding, and peaceful

European integration who was forced out of Europe and died in isolation far

from home in Brazil, while on the other side we have the

Zionist and pioneering scholar of kabbalah whose search for the deep historical

and existential roots of his Jewish identity led him to leave Europe behind of

his own volition to build a new home in Palestine. The American author George

Prochnik has published an impressive biographical diptych about these two

famous personalities and their very different experiences and perspectives: The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World was published in 2014, and Stranger in a Strange Land: Gershom Scholem and Jerusalem came out in 2016. I found these

two books to be full of valuable insights that carry deep relevance for the

political and cultural conflicts we are currently experiencing. Just like about

a century ago, once again we find the Humanistic and Enlightenment ideals of “cosmopolitanism

and secular liberalism” pitted against the Counter-Enlightenment forces of “nationalism,

religion, and identity politics.” What can we learn from comparing Zweig and

Scholem?

“I love the Diaspora,” Zweig wrote to Martin Buber in 1917.

He went on to explain that he had “never wanted the Jews to become a nation

again and thus to lower itself [sic] to taking part with the others in the

rivalry of reality” (Exile, 134). When Buber responded by restating his Zionist

convictions, Zweig insisted: “the more the dream threatens to become a reality,

the dangerous dream of a Jewish state with cannons, flags, medals, the [sic]

more than ever am I resolved to love the painful idea of the Diaspora” (135). Zweig

felt perfectly at home in his native Austrian culture because he considered

himself a citizen of Europe and the international republic of letters. Frankly,

he could afford it. Born in 1881 in a very affluent Jewish family in Vienna, he

seems to have been absolutely fine with both the ideals and the realities of

cultural and ethnic assimilation that had worked out so beautifully for him. Almost to

his own surprise – he never had a particularly high opinion about himself as a

writer – all doors to fame and success seemed to open almost by themselves and

he enjoyed a dream career as a writer. The world was his oyster.

| |||

| Gershom Scholem at twenty-seven |

What a difference with Scholem! Born in 1897 as the son of a printer

living in Berlin, he was sixteen years younger than Zweig and rebelled

violently against his bourgeois father with his strong assimilationist views. If

Zweig felt he belonged to the German people (meaning the German-speaking peoples

of Europe), Scholem would later dismiss such feelings of belonging as “a lurid and tragic

illusion” for Jews, even on the level of culture alone (147; Stranger, 9). While Zweig was a typical

representative of Liberal Humanism in the tradition of his hero Erasmus,

Scholem’s deep concern was with his Jewish identity and he became a vocal activist

on behalf of the Zionist cause. For Zweig, leaving Europe meant exile. For

Scholem it meant liberation.

The Cosmopolitan Idealist

Reading Zweig’s autobiography Die Welt von Gestern (The World of Yesterday) in tandem with

Prochnik’s The Impossible Exile about

Zweig’s final years means receiving an introduction to the original meaning of Liberalism

as an ethical and humanitarian ideal with deep roots in European history. Zweig

had no sympathy for the American culture of capitalist consumerism that – especially

in the form of its radical “Neoliberal” upgrade since the 1980s – is so often

confused with Liberalism today. On the contrary, he felt that “global dance

crazes, mass fashion, popular cinema, et cetera were leveling the cosmos of

human expression ‘into a uniform cultural schema’,” and feared that “[t]he

United States had inaugurated a ‘rush into servitude’ of the masses, clearing

the way psychologically for dictatorships of every variety to seize power. If

the Great War marked the first phase of Europe’s destruction, he concluded,

‘Americanization is the second’” (Exile, 235-236). Of course such words sound

uncannily prescient today. In fact, reading Prochnik’s description of how the

refugee Viennese psychoanalyst Ernst Kris discussed Hitler, I could not help

noticing that he might as well have been talking about Donald Trump. The principles of demagoguery seem universal:

[Hitler] once said the masses were so dumb

and so feminine, they would take anything you told them, so long as it was

expressed in the manner of advertising catchphrases. “Truth is of no avail, but

there must be an ideology behind it, something to inspire the imagination,”

Kris explained (152).

As an alternative to the degenerate culture of American

consumer capitalism, Zweig did not

advocate a return to nationalism or a revival of populist Blut und Boden sentiments but quite their opposite: a Pan-European

humanism grounded in tolerance and mutual understanding as guiding ideals that

should be passed on from one generation to the next by means of responsible

education, or Bildung. His confidence

in this approach seemed boundless:

Reverence for Bildung, that magically potent idea of holistic, rigorously

intellectual character development, predicated on fluency in the canon of

Western knowledge, had made it impossible for educated Germans to take Hitler

seriously, Zweig wrote. It was simply inconceivable that this “beer-hall

agitator” who had not even finished high school, let alone college, “should

ever make a pass toward a position once held by a Bismark, a Baron von Stein, a

Prince Bülow.” In consequence, Zweig said, even after 1933 the vast majority

still believed Hitler was only a kind of stopgap, and that the Nazis would

prove a transient phenomenon.

What Zweig did not make explicit in his memoir was that

he’d made this mistake himself. No one placed a greater trust in the redemptive

power of cultural education than did Zweig, who expressed his faith, even after

Hitler’s appointment as chancellor, that the Third Reich would prove only a

brief hiccup en route to the unification of Europe – the coming “world

Switzerland,” as he labeled it. It took years for Zweig to really absorb the

notion that the masses’ indifference to intellectual and cultural achievements

might be a lasting condition. … The best response to Hitler’s popularity was

not to demonize his supporters, Zweig believed, but to communicate to them the

value of the rich German cultural legacy that was being jeopardized by Nazi

politics (62-63).

Today, of course, it is very easy for us to dismiss such statements as tragically naïve – much easier, in any case, than it

is to explain how and why an attitude of dismissive cynicism about such

highminded ideals should be any more likely to succeed! As Prochnik puts it – and

I agree –, “Illusions are not to be eliminated but encouraged, since only the

powers of imagination can summon a vision of a more humane future” (255). Zweig

did believe deeply in the value of building bridges, by cultivating generosity

and empathy (137) instead of hatred and suspicion. Seeking out alternatives to

the privileged milieu of his own upbringing, during his younger years he spent

much of his time “at motley bars and cafés squeezed between ‘heaving drinkers,

homosexuals and morphine addicts’,” for (as he commented) “the worse someone’s

reputation was the more I wanted to know him personally” (90). This fascination

with the so-called “losers” and social outcasts who populated the seedy underbelly of bourgeois

society was linked to an acute ethical awareness that “between power and

morality there was rarely a bond but rather an unbridgeable gap” (358). The

power that came with his own position as a famous writer never seems to have

blinded him to the moral arbitrariness of the privileges he enjoyed. In other

words, he never thought that his talent and success made him “better” than

others. Having been accepted as a refugee by several countries in succession, these

are his words to one of his benefactors in the last of them, Brazil:

You have been kind enough to honor me, to

welcome me among you. I should feel proud and happy. But I must confess to you

that at a time like this I am not able to feel happy and still less to feel

proud. On the contrary, I feel heavy at heart that you should show me such

friendship while countless people, our own and others, are suffering. We as

human beings, and especially as Jews, have no right in these days to be happy.

… We must not imagine that we are the few just people who have been saved from

the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah because of our special merits. We are not

better, and we are not more worthy than all the others who are being hunted and

driven over there in Europe (208).

The inevitable counterpart to Zweig’s humanitarian idealism was

the deep despair he felt about the collapse of European culture and

civilization caused by the Nazi takeover: as Prochnik puts it, towards the end

of his life he seems to have lost all hope because he had “ceased to believe

his works were part of any larger edifice” (259). He was haunted by

premonitions of catastrophe, years before they became reality: “my nose for political disaster

tortures me like an inflamed nerve” he told Joseph Roth in 1936 (130, cf. 218,

285). Just days before the Anschluss

he was watching in helpless horror as his fellow-Austrians were blissfully

doing their Christmas shopping and going about their daily affairs: “Don’t you

understand? All this will be gone in a few months’ time. Your homes will be

plundered. Your clothes will be changed for prison garb” (176).

Prochnik

gives much attention to the international refugee crisis that followed the Nazi

takeover: “The trickle. The stream. The flood. And then people surging all over

the globe, falling from the skies, splashed up by the seas, hurled

helter-skelter by the wildly spinning red-and-black wheel” (204). In an

analysis that should sound bitterly familiar to us today, he points out that

even though the numbers of refugees that actually made it to America were

astonishingly small, intentional propaganda and general paranoia caused many

Americans to believe that their country was overrun with “millions of

refugees,” “swamped with exiles to the point where millions of jobs and

democracy itself were at risk” (205). Where have we heard such things before? For Zweig personally, exile brought the

bizarre realization that while his “intellectual fatherland” no longer considered

him to be German, the British did classify

him as “German,” that is to say, as an “enemy alien” (164-165). In short, he

found himself rejected by both Germans and non-Germans.

What then about his Jewish identity? It

didn’t help either. In a highly illuminating passage, Prochnik points out that

for Zweig, the defining experience of exile turned out to be that of “being

forced to identify with people who bore no relation to him” (164). He wrote

that most Jews in Western Europe had no clue about why they were being thrown

together for persecution (163):

[they were] no longer a community and had not

been one for a long time. They had no law. They did not want to speak Hebrew

together. Only exile swept them all together, like dirt in the street. … If

Shylock’s famous question – “If you prick us, do we not bleed?” – was intended

to show that the Jews share a common humanity with all mankind, Zweig

approached the injustice of anti-Semitism by revealing the total absence of

common ground between the Jews themselves (164).

And that brings us to one of the most harrowing passages in

the book, at least to this reader. Prochnik begins by discussing the famous

passage in the 2nd chapter of Mein

Kampf where Hitler describes how he became an anti-semite. On the streets

of Vienna he saw an orthodox Jew in a long caftan with black curls, and found

himself wondering “Is that a German?” His conclusion was that only the German

language made it possible for Jews to pass as real members of the Volk: in fact they were cosmopolitans

who could “speak a thousand languages,” and “if they ever got into power they

would force everyone to speak an international language such as Esperanto”

(155). From there, Prochnik cuts straight to a scene shortly after Zweig went

into exile. He spent an evening in a Yiddish theater in London together with

Otto Zarek, where they watched a performance about Jewish ghetto life in

Russia:

… after the show Zarek was struck by Zweig’s

state of acute nervous agitation. He could not contain his inner excitement.

“These old Jews,” Zweig said, “in their grotesque dresses, their beards

unshorn, their eyes flaming, these adherents to Chassidism … they are our brethren.” It was only the measures

toward assimilation taken by their great-grandparents that had kept them from

looking just like those Jews did, Zweig told Zarek. Had it not been for their

near forebears, the two of them would have ended up “believing in what they

believe,” considering “our life in the midst of the Western world as just a

transitory period – we, too, would harbour in our very hearts, the dreams of

our eventual ‘return to the land of our forefathers’.” Zweig comes within a

hair of saying, “There but for the grace of God.” But Zarek said that Zweig’s

voice took on a note of despair and resignation, as he registered that he

hadn’t, after all, quite dodged the bullet (156).

Prochnik hardly needs to spell it out. To his enormous

distress, Zweig was experiencing the very same kind of instinctive prejudice

that had made Hitler an antisemite, and of course he was far too

sensitive and intelligent not to realize it. In his own life he had always

sought to emulate the spirit of Schiller: “I write as a citizen of the world.

Early did I exchange my fatherland for mankind” (156). But now Hitler had

deprived him of the community of language that constituted his true spiritual

fatherland, and - not unlike what happens to the rich kid in Bob Dylan’s “Like a Rolling Stone” - those outcasts and “others” with whom he felt no spontaneous

kinship had suddenly become his closest brethren whose company he could not

avoid: “go to him now, he calls you, you can’t refuse…”

Once upon a

time Zweig had told Buber that he loved the diaspora, but now he had become a

refugee himself and there was nothing he loved about it. He was longing not for

the land of Israel (it struck me that he never seems to have considered seeking

refuge in Palestine), nor for the Austria in which he had grown up. He missed Europe: his invisible community of the

spirit, his universal republic of humanitarian brotherhood, his true

cosmopolitan fatherland that represented inner freedom and unlimited

possibilities, a land without borders that would welcome all comers. This was

his true home, and it had come crashing down all around him. In the long run,

the loss proved unbearable. On 22 February 1942, Stefan Zweig was found dead in

his Brazilian home. He and his young wife Lotte had committed suicide together.

|

| Stefan and Lotte Zweig on their deathbed |

Quite like his model of Enlightened Liberal

Humanism Erasmus (whom he painted in sharp contrast to Luther as the archetypal “fanatic” with evident traits of

Hitler), Zweig had never been a fighter. “I can only write positive things; I

can’t attack” (65, cf. 290). Irmgard Keun once described this natural-born

pacifist as “one of those noble Jewish types who, thin-skinned and open to

harm, lives in an immaculate glass world of the spirit and lacks the capacity

themselves to do harm” (246).

In this regard his disposition could not have been more different from that of Scholem. While Zweig was ultimately powerless to defend himself against the forces that destroyed his glass world of the spirit, Scholem seems to have been born a rebel and a firebrand, a fighter by nature. It would seem that throughout his life, the only way he could conceive of anything whatsoever was in terms of dialectical struggle ruled by the paradoxical logic of coincidentia oppositorum. For Zweig, losing all hope could only mean that no hope was left – obviously. But Scholem’s logic worked differently: “In his final years he was very hopeless. He said that now the only thing that remained was hope,” his widow recalled (426). The paradoxicality of such a remark has Scholem written all over it.

The Dialectical Zionist

In this regard his disposition could not have been more different from that of Scholem. While Zweig was ultimately powerless to defend himself against the forces that destroyed his glass world of the spirit, Scholem seems to have been born a rebel and a firebrand, a fighter by nature. It would seem that throughout his life, the only way he could conceive of anything whatsoever was in terms of dialectical struggle ruled by the paradoxical logic of coincidentia oppositorum. For Zweig, losing all hope could only mean that no hope was left – obviously. But Scholem’s logic worked differently: “In his final years he was very hopeless. He said that now the only thing that remained was hope,” his widow recalled (426). The paradoxicality of such a remark has Scholem written all over it.

This

profoundly dialectical mentality ruled Scholem’s life and career. I consider it

the key not only to understanding his concepts of Zionism and of Jewish mysticism,

but ultimately to understanding everything

he ever did or thought. Consider the following list of conflicts and oppositions,

which makes no claim to completeness:

Scholem emigrated “from Berlin to Jerusalem” in spite of (or rather, I suspect, because of!) his core conviction that Zion was a messianic dream that could not and in fact should not be realized in this world. As a scholar searching for the roots of authentic Judaism, he explored the broader world of Hellenistic “paganism” and its legacy: I think he was driven by an intuition that the secret of Jewish life could be found precisely in the culture of the idolaters. As a model “historian’s historian,” he insisted on strict philology and textual criticism but applied these methods precisely to the “non-historical” world of mythical symbolism that appeals to the imagination rather than to strict literalism. While Jerusalem was in a state of siege, and extreme violence was rampant, he sat down to write a famous essay (analyzed at length by Prochnik) exploring the notion of “redemption through sin.” Scholem’s life-long search was for the authentic secret at the heart of Jewish tradition, as an alternative to the Germany he rejected, and yet the hermeneutics that allowed him to discover Jewish secrets was grounded in German scholarship, German Idealism, German Romantic speculation. He never ceased emphasizing that der Liebe Gott lebt im Detail, so that only by focusing on the particular and the unique could one gain lasting insights and discover general or even universal truths - and yet, he knew that without such general perspectives and a search for the universal, one would never succeed in opening the closed shell of the particular in the first place, and would fail to discover its hidden contents. Scholem could be described as a Jewish representative of the interwar “conservative revolution” who tried to impact the future of Judaism not by rejecting past traditions but by preserving and reviving them. In short, Scholem was a modernist struggling (like all modernists) with modernity itself. He was a rationalist driven by the energy of the non-rational: “my secularism is not secular” (58-59).

Whereas Zweig’s despair ended up killing him, Scholem’s dialectical mindset seems to have enabled him to use it as a creative force, as he wrote in a letter to Hugo Berman in 1947: “I live in despair, and only from the position of despair can I be active” (Briefe I, 331). In an earlier discussion of Scholem, I concluded that, for him

… the fact that eternity cannot appear in

time mean[t] that the hope that sustains Jewish identity through history can

only be called an “aspiration to the impossible.” Under these conditions, the

historian must have the courage to “descend into the abyss” of history, knowing

that he might encounter nothing but himself, and guided by nothing but a

desperate hope for the impossible: that against all human logic, the

transcendent might inexplicably “break through into history” one day, like “a

light that shines into it from altogether elsewhere” (Hanegraaff, Esotericism and the Academy, 297).

Prochnik reads Scholem’s story as a mirror of his own. His

book consists of two interwoven narratives, one of which traces the first four

decades of his subject’s life (from his adolescent years of Sturm und Drang in Berlin to his

reaching maturity as a scholar in Jerusalem during the 1930s), and one that

describes his own deeply personal search for an authentic Jewish identity that led

him and his wife Anne to emigrate from New York to Jerusalem in the mid-1980s. Scholem’s

beginnings were very different from Prochnik’s though. He depicts himself and

his wife as a couple of young starry-eyed idealists driven to Jerusalem on the wings of “a

dream of compassion” (87). By contrast, the young Scholem was an angry

extremist who “went into overdrive” (109) around the age of seventeen:

Thinking about the collapse of Europe led him

to picture the Land of Israel as a kind of womb, streaming with the ages,

awaiting insemination. … Scholem took solitary walks … during which he would

scream out speeches that he ordinarily whispered. People stared at him, and he

blushed. … He imagined a novella about his own suicide … “I would shoot myself

after concluding that there was no solving the gaping paradox in the life of a

committed Zionist.”

Paradoxes, rages, fears, and desires were

flying off the fabric of his being like burst buttons and seams. Raving on the

street in some paroxysm of humiliation and fury, he might have hurled himself

in front of a train or off a bridge. He might also have leaped on his father

with any weapon at hand. He seems to come within a razor’s breadth of some

irrevocable act of destruction. Scholem’s whole story might have ended before

he ever reached Jerusalem. He craved too desperately for an impossible purity

(110).

Reading such passages, I could not ignore the contemporary parallels,

uncomfortable as they might be. Prochnik describes a youthful Zionist hothead,

in full rebellion against his father’s demand that he sacrifice his Jewish

identity by “assimilating” and becoming an obedient member of German bourgeois society. Today we have the

phenomenon of youthful Jihadist radicals born in the West, who likewise refuse

the dictates of cultural “integration” and declare total war on Liberal society

in the name of Islamic purity. Scholem’s brand of Jewish identity politics

seems an extreme counterpart to the Liberal universalism represented by

intellectuals such as Zweig, and often enough he would find himself brandishing

“the torch of ethnic-historical particularity against the ambient moral glow of

universal ideals” (105).

Still it is important to emphasize that,

for all his violent feelings of revolt, Scholem’s Zionism was predicated on the

ideal of a peaceful settlement between Jews and Arabs. Having arrived in

Jerusalem, he became a core member of the Brit

Shalom (Covenant of Peace) movement that would later be described by one of

its founders, Hugo Bergmann, as “the last flicker of the humanist nationalist

flame, at a historical moment when nationalism became among all the nations an

anti-humanist movement” (304). Sympathetic as its ideals might be, Prochnik does

not spare his critique: Brit Shalom’s

slogan “Neither to dominate nor be dominated” sounds somewhat less commendable if

one realizes that its “commitment to absolute political equality with the Arabs

was presumptuous at a time when Jews were still less than 20 percent of

Palestine’s overall population” (305). Likewise, Scholem’s commitment seems to

have been inspired more by “his aspirations for the ideal manifestation of

Zionism” (307) than by any deep sense of fellowship with his Arab neighbors.

Prochnik does not try to conceal the

similarity of such attitudes to those of Anne and himself during their years in

Jerusalem. Like Scholem, they desperately wanted to believe

in the Zion of their dreams, but they had trouble seeing what was actually

going on all around them in the state of Israel. Wondering what it must have been like for Scholem to

enter Jerusalem for the first time, in late September 1923, Prochnik expresses

doubt about whether the actual land of his forefathers had any reality for him at all:

A chorus of support arose from amid the

crowd: “In blood and fire we will do away with Rabin!” Torches were hurled at the police monitoring the demonstration. Chants of “Bibi! Bibi!” alternated with choruses of “Nazi! Nazi!” as images of Rabin with his head at

the center of a bull’s-eye framed with the word “Traitor!” in Hebrew and

English were brandished aloft (356).

In this violent context of populist hate-mongering, it appears that some

enemies of the peace process resorted to kabbalah, in a particularly cruel

refutation of Scholem’s attempts (rightly criticized by Prochnik, with

reference to the scholarship of Jonatan Meir, 252-258) to deny it any relevance to

modern and contemporary society:

|

| Leaflet "Song of Peace" with Rabin's blood on it |

Yigal Amir, Rabin’s assassin, performed

mystical rites just before pulling the trigger. As Rabin stood above him on the

stage singing “Song of Peace,” Amir waited in the darkness, practicing the

esoteric art of Gematria … Concentrating on lines from Genesis … a passage

that includes the line “a smoking fire pot and a flaming torch passed between

these pieces” – Amir found that by sliding forward one letter from each word to

join the following word, the words “a flaming torch passed between” transformed

into “fire, fire, there is evil in Rabin.” And then Amir knew his bullet would

strike home (357-358).

Rabin’s assassination killed the dream: “Our sense of magical

solidarity with the Land and the people dissipated like smoke after an

explosion” (378). George and Anne Prochnik packed their things, took their children, and fled the scene: “Clutching the children. Clutching each

other, we were blown into the air forty thousand feet above the earth and cast

through the sky to America” (409). Back home they discovered that the end of

their dream of compassion meant the end of their marriage as well.

... and all that remains is hope

Prochnik’s two books have at least one obvious thing in common: they are all about broken dreams. Zweig’s Humanist dream of Europe was destroyed by Hitler – so cruelly and so completely that he saw no future and decided to kill himself, taking his wife with him. Scholem’s Zionist

dream suffered shipwreck on the hard rocks of nationalist Realpolitik; the German culture that had nourished his very understanding of Judaism was reduced

to smoking ruins; and his people were murdered on an industrial scale and with a maniacal determination that defies imagining. As for Prochnik’s mystical and messianic dream of

Jewish community - grounded as much in his understanding of Scholem’s antinomian

dialectics of kabbalah and modernity as in the liberal and humanitarian idealism represented by Zweig -, it was blown to pieces by Yigal Amir and transformed into a cruel

nationalist Blut und Boden caricature by orthodox fanatics and right-wing

politicians.

Stories of failure and the loss of illusions. So what is the point? Why bother reading about dreams that do not come true - while nightmares do? Are we to conclude simply that all these highminded ideals about a better world and all these aspirations towards a better future are bound to end in

disappointment and despair, leaving the final word to violent hatred, bloodshed, fanaticism, cynism, nihilism, power, and domination? Was it all in vain? Of course Prochnik asks himself the same

questions, and he ends by quoting a wonderful legend about the Baal Shem that was told by Scholem

at the end of Major Trends in Jewish

Mysticism. Scholem in turn had heard it from the novelist S.J. Agnon, who might

have found it in a Hasidic collection published in 1906. Its point is that

even when all seems lost and gone forever – “when the sacred fire can no longer be lighted, the prayers

can no longer be spoken, and the sacred place is no longer known” – in the end it is sufficient that the story can

still be told. Perhaps this might explain why even stories that end badly, like those told by Prochnik, have the power - paradoxically - to inspire their readers rather than leaving them crushed and defeated. It is of vital importance that such tales be told, for they are all about hope, and hope remains alive as long as its memory remains alive - after all, whatever can

be remembered in our personal or collective imagination can be imagined as real, and whatever can be

imagined as real has not lost its potential of being realized. Sometime. Somewhere. Somehow.

Thank you for this post. I thought you might be interested also to know about the publication of Scholem's intellectual biography (Chicago UP)

ReplyDeleteMore here: http://www.press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/G/bo25126030.html